The 61st Berlin International Film Festival

By Leslie Weisman, DC Film Society Member

Fest directors rarely draw attention to empty seats, and with some 300,000 tickets sold to the more than 400 films from 54 countries represented at this year’s Berlinale, Dieter Kosslick would have been hard pressed to find one. But he did — and drew the world’s attention to it. Because the empty chair was a juror’s chair, to have been filled by the renowned Iranian director Jafar Panahi whose award-winning, intensely humanist films (including Offside, Crimson Gold and The Circle) and participation in demonstrations against actions by the regime have made him the repeated target of government reprisal.

Photo from the Berlin International Film Festival website.

Just weeks before he was to serve on the Berlinale jury, Panahi had been condemned by an Iranian one (perhaps literally “one”: in most such trials, the judge serves not only as judge but as prosecutor, jury, and arbiter) to serve six years in prison. And in a blow not only to Panahi but to the world, the filmmaker was banned for 20 years from making movies, writing screenplays, giving interviews, or leaving the country.

But he did leave the country, at least metaphorically. Not only were five of his films (including the aforementioned) screened; his absence and his legacy were part of the conversation throughout the festival, as actors, directors, reporters and jury members invoked his name, making his enforced silence a defiant shout that would reverberate around the world.

“The world of a filmmaker is marked by the interplay between reality and dreams,” wrote Panahi in an open letter read by jury president Isabella Rossellini to a rapt crowd in the Berlinale Palast at the festival’s opening. “The filmmaker uses reality as his inspiration, paints it with the color of his imagination, and creates a film that is a projection of his hopes and dreams.

“The reality is I have been kept from making films for the past five years and am now officially sentenced to be deprived of this right for another twenty years. But I know I will keep on turning my dreams into films in my imagination....

“I submit to the reality of the captivity and the captors. I will look for the manifestation of my dreams in your films, hoping to find in them what I have been deprived of.”

If Panahi has dreamed in 3D, he was indeed at the Berlinale, where even the festival promo preceding each film began with a brilliant, slow-mo, mesmerizing 3D explosion of golden stars that transformed themselves into the festival logo. The technology itself gave evidence of having won over filmmakers at both ends of the professional and generational spectrum. Sixty-five-year-old master Wim Wenders, certainly no stranger to innovation (New German Cinema, anyone?), whose Pina had German Chancellor Angela Merkel happily donning 3D glasses for the film’s premiere in the majestic Berlinale Palast, averred to the Berliner Morgenpost that “I can only film in 3D now.” (Note: All translations from the German are this writer’s, including comments by native English-speaking actors and directors that were translated into German for publication in local newspapaers and magazines.)

Wenders’s message was not lost on young up-and-coming directors at the Berlinale Talent Campus, a week-long, intensive series of workshops initiated by Kosslick four years ago to bring together young talents and filmmaking professionals from around the world to learn from master filmmakers, and from each other. Scores of “talents” listened attentively as Wenders described how his almost quarter-century-long aspiration to make a film about the inimitable yet highly influential German choreographer Pina Bausch — whose tanztheater, a mixture of dance and theater, depends upon the dancers’ own emotions and memories and the director’s ability to draw them out and incorporate them — for a long time seemed fated to remain just that. “What I admired most about Pina’s art was the reason not to make the film,” said Wenders, who has called her the “discoverer of a new art.”

“There was something almost untranslatable, immediate, physical, about her work” that went beyond the bounds of traditional cinema, he told the talents. “Between my cameras and Pina’s art, there was a wall; I didn’t have the tools to go there. But 3D opened the door into the realm of Pina’s dances, their immediacy and physicality.”

Wim Wenders at the press conference. (Photo from the Berlin International Film Festival website).

And then ... a door closed, with jarring immediacy and physicality: Bausch died, just five days after receiving a diagnosis of cancer, at the end of June 2009. At first Wenders announced that he was abandoning the project, but Bausch’s dancers convinced him not to give up on something that had meant so much to them both. (“That was our running gag, whenever [Pina and I] saw each other in the world,” Wenders told the Berliner Morgenpost. “When!?” — “When I know how!”) The result is a passionate hommage to Bausch and her work.

Curiously, the jury is still out on whether the film, and by extension 3D, will be good for dance and dance theater. As a Morgenpost writer observed at one point as he alternated between admiration and uncertainty regarding Pina, “Until now, film was the wrong medium for dance,” something “flat” in which the absence of live performance was keenly felt. “But suddenly, film becomes a real threat to the theater, because here dance is even closer, even more elemental” than it is on the stage. True enough: Here, the dancers leave the stage, go outside and “conquer” it, as well, turning the everyday into the magical. We follow them, breathtakingly alive, as they dance in, through and across a street, a park, a river, a factory and a railway car, Wenders’s savvy and sophisticated use of 3D infused with a childlike wonder that intensifies the viewer’s experience.

For Pina is a film that employs 3D not in the service of spectacle, but — as Green Party head Claudia Roth, calling it “one of the greatest film experiences I’ve ever had,” told a reporter: “You’re suddenly right there, in the center of this world of feeling. I’ve never experienced anything like it.” (The New Zealand Herald went a step further: “This movie is so beautiful it aches.”) Indeed, unlike films such as the Oscar-winning, wow-how-did-he-do-that Avatar (“For Pina,” Wenders told epd Film, “my greatest dream is that after 10 minutes, you forget the medium”) — which no one would mistake for a documentary — Wenders sees the future of 3D precisely in that mode. “I can imagine that in a few years, nobody will be seeing documentary films in anything but 3D. Look: In the mid-‘90s, the documentary film was as good as dead. With the new digital techniques, the genre has practically been rediscovered.”

Almost as if to prove the truism that for every rule there is an exception, of the two additional 3D films of note that would screen here, one was about as far from a documentary as you can get: a fictional animated film in the style of legendary silhouette animator Lotte Reiniger whose protagonists recreate scenes from international folk tales. The second was indeed a documentary, whose title with seeming prescience would gain a poignant layer of resonance in the light of Panahi’s moving invocation.

The allure of 3D was demonstrated in a very personal way for your reporter early on a Sunday morning when, on a hunch, she arrived for Tales of the Night (Les contes de la nuit, Michel Ocelot, France 2011) nearly an hour before screening time and found five intrepid pressies already out there, waiting patiently in the frigid air. As the time passed we would smile or shake our heads as each new arrival without fail tried the locked doors — some insistently or even angrily, as if in disbelief, despite the early hour, that their obvious need, their press-pass-given right to enter the Palace would not cause the doors to open for them. (Like something out of a fairy tale.”)

It was worth the wait. Tales of the Night is one of those kid-friendly films whose charms will reach out to adult audiences with its blend of innocent wonderment, sophisticated humor and technical wizardry. “I’ve never made films for children,” Ocelot told The Hollywood Reporter. “That’s why children like my films. Nobody wants to be treated as a baby.” But we are willing to have our inner child spoken to.

Every night, a girl, a boy and an elderly technician meet in a little cinema that seems abandoned, but is in fact full of wonders. The three friends research, draw, invent, dress up and act out the stories that take their fancy in a magical night where anything is possible — sorcerers and fairies, powerful kings and stable boys, werewolves and merciless ladies, cathedrals and straw huts, cities of gold and deep forests, the waves of harmony of choirs immense and the spells of a single tom-tom, malice that ravages and innocence that triumphs…

His words have the soothing, hypnotic rhythm of a bedtime story. And the tales the film presents in rich, gorgeous hues, strikingly contrasted with the pure black silhouettes of the human characters, all drawn and designed by the multi-talented Ocelot (“You’re a writer, director, artist, production designer, animator, editor, cinematographer and former president of the International Association of Animated Films. When do you sleep?” The Hollywood Reporter demanded), are cast in the form of dreams (Panahi!). The fairy tales, which are a passion of the director — “Fairy tales have a hidden power... They’re the best way to get messages across” — are laced with the wisdom of the ages, reaching across continents to tap into the ancient storytelling treasures of Europe, Asia, and South America.

You can’t get much more ancient than the messages discovered by Werner Herzog in his latest (and first 3D) film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, named “one of the ten most-hyped TIFF 2010 films” by Torontoist and celebrating its European premiere at the Berlinale. Inspired, and to an extent driven, by the lingering memory of “the shudder of awe and wonder” evoked by a volume of cave paintings he’d spotted in a bookstore window more than half a century before as a boy of twelve, Herzog followed his own unforgotten dreams to the Chauvet Cave in southern France, on whose walls are inscribed “the earliest known visions of humanity” dating back over 30,000 years.

Gaining access to the inside of the caves was no mean feat: to protect the fragile paintings from exposure to elements from the outside world that could damage them irreparably, the French government had rejected all requests from filmmakers to record them. Until, that is, the redoubtable Herzog — the man who, among other things, ate his shoe on a bet and filmed it; tamed the legendary “wild beast” Klaus Kinski and made a film about their tortured, decades-long relationship in the aptly titled My Best Fiend; calmly continued a televised interview after being hit by an air-rifle pellet fired by a crazed gunman, observing that it was “not a significant one”; and walked from Munich to Paris to keep a terminally ill friend alive (no, not to gather pledges, but because he reasoned that she wouldn’t dare to die before seeing him again) — made the minister of culture an offer he could not refuse. He would, at least for a time, become a French government employee, for which he would accept a salary of one euro. And pay taxes on it.

At least, that’s the story, tongue-in-cheek though the last part may be. In any event, Herzog and a small crew were allowed, with severe restrictions, to film inside the cave for a couple of weeks. Their job was made more difficult (not to mention precarious) by having to balance with their cameras on the narrow metal catwalks spanning the cave, and by the high levels of radon and carbon dioxide that make it impossible for them to work for more than a few hours a day. And the use of 3D was “imperative,” Herzog told Screen Daily: “Since my film in the cave may be the only one ever permitted to be shot there because the climate is so delicate, you had to bring the audience into the cave itself.”

In anticipation of its screening, which the director was unable to attend because he was in Houston shooting a new documentary about death row in the U.S., Herzog gave a telephone interview to Spiegel Online as he prepared to visit a maximum security prison. “You have to realize that, about 20,000 years ago, there was a cataclysmic event when an entire rock face collapsed and sealed off the cave. It’s a completely preserved time capsule,” he said. Herzog minced no words in assessing the cave’s importance. “This is the birth of the modern human soul. The artists are like us, not like the Neanderthals, who had no culture — and who incidentally were still roaming the landscape at the time the paintings were made.”

Why 3D? Herzog hasn’t jumped on the bandwagon for the new technology, calling himself “in general ... skeptical” about its use. But here, “you have these enormous niches, bulges and protrusions, as well as stalactites and stalagmites. The effect of the three-dimensionality is phenomenal.”

Technical three-dimensionality is not the only kind that would prove a boon to many a cineplex film whose characters sometimes struggle to achieve two. By contrast, this year’s opening night film, first-time director J.C. Chandor’s star-studded yet intellectually and emotionally complex Margin Call, takes on a subject and people often dismissively written off by most of us, and peels away the layers of prejudice and self-righteousness with which those of us on the outside have come to regard them.

Not the poor, and no, not the homeless; not even the street people who imploringly hold out cups or hats as we busy, important people try to get where we’re going. No: The once powerful and secure, now broken, beleaguered, frightened men and women who are treated with a measure of respect and compassion in Margin Call are ... investment bankers.

If the Wall Street movies pretty much confirmed our suspicions that, as Roger Ebert memorably wrote, “Gordon (‘Greed Is Good’) Gekko became the role model for a generation of amoral financial pirates who put hundreds of millions into their pockets while bankrupting their firms and bringing the economy to its knees,” Margin Call asks us to look at the human beings who were caught up in the catastrophic financial meltdown. The ones who, as Kevin Spacey declared at the press conference, “are just regular people who have regular jobs and aren’t making gazillions of dollars and in many cases had to follow orders.

“And that’s the crux of the morality of the piece,” he continued, “and why I found it so fascinating to humanize a character” — Spacey plays an executive at the firm — “the kinds of people who had been dehumanized for so long. It’s very easy, I think, and a bit lazy, to put everybody in the same wheelbarrow.” That’s something Chandor does not do, and for a good reason, besides the basic one of fairness: as the son of a father who worked for Merrill Lynch for almost 40 years, Chandor had a “fundamental knowledge of the people in this world and most importantly had a strong understanding of what and who they cared most about.”

Chandor, who in addition to directing wrote the screenplay, was adamant that the film, which has a tense energy that turns terrifyingly desperate as the walls inexorably begin to close in on everyone at the firm from the top execs to the temps, remain focused on the human side and the human cost. “I tried to look at it with a more sympathetic eye on both sides. It’s not like I’m a banker who is defending other bankers, but also knowing a lot of these people, you recognize that it’s not pure evil, either.” At the press conference, Chandor added: “To me, the film is a tragedy. You see people who have wasted a good bit of their lives....”

Jeremy Irons, who plays the big-gun CEO who comes in to issue the edict that will supposedly save the company — but at the cost of its “nonessential” employees, and stockholders’ assets — mourned the “amoral[ity]” of the banking industry. “We have to care about the fact that people are having their houses taken away from them, we have to care about the fact that people have borrowed sort of beyond their dreams... We live with limited resources in this globe and we have to find a way to share those resources so that everybody’s relatively happy, has a job, has a roof, and not allow consumerism to go rampant, which it has been allowed for twenty, twenty-five years. I suppose that’s what I feel, but my role . . . he was an amoral man who just wanted to keep the ship afloat. And would do anything to keep the ship afloat because that was his job.

“But we have to add something else to the mix, I think. As far as the people who are making the big decisions globally. And there has to be morality.”

The cast visited Wall Street firms to get a feel for the culture and learn about the people who work there to inform their portrayals and their understanding of their characters. Paul Bettany, who plays a mid-level exec, found it “a really interesting journey, and I think I became a lot less judgmental because of that process.”

In response to a question, the discussion turned to an exchange about the film industry. “I don’t know that it’s ever been easy to raise money to make films if they’re not being backed by large corporations and studios,” said Spacey. “We can go back into the beginnings of the independent film movement and see that every single director or producer has always had a sort of remarkable story of how they managed to [cobble] it all together.

“What has become more difficult I think as the result of the financial crisis is that distribution for independent films has become much more difficult. So that what ends up happening is there’s a sort of cycle in which if a film that perhaps is a wonderful story and has a great cast and is directed well even gets a release, but it’s such a small release that it doesn’t make money its first two weeks, then the theater owners want it out and they want the next one in, and that then in turn makes it harder for the next independent film.

“I wish and hope that we could return to the days that the major studios had ‘arms’ for independent film — if you look at some of the work that was done even a decade ago in the film industry, from the sort of specialized arms of the major film companies, rather than them only going out and finding movies like this at film festivals...

“I [see] nothing wrong with the tentpole movies or the franchise movies, but I wish they’d take some of those proceeds and make ten great, small films about stories that should and need to be told. So yes, it’s more difficult, it’s more challenging. But I also am a big believer that if you have a story you absolutely must tell, that you will find a way to tell it.”

The film’s impressive cast includes, in addition to Spacey, Bettany and Irons, Demi Moore, Simon Baker and Stanley Tucci. U.S. release was scheduled for March 23, when it opened at Lincoln Center in New York.

“... if you have a story you absolutely must tell ... you will find a way to tell it.” In theory, those words could apply to virtually any independent filmmaker. But for those living in countries where freedom of expression is regarded not as a right, but as a threat, finding that way can be more than difficult, more than challenging. It can be outright dangerous.

“Sacrificial oligarch” is not a phrase that flows easily across the tongue. Nor is the person such a term might describe very easy to conceptualize. Then again, neither is the name — or the man — Mikhail Borisovich Khodorkovsky, to whom the phrase refers in ExBerlin’s article about the eponymous documentary by German director Cyril Tuschi. The thieves who stole the film out of his office along with four computers just days before its official premiere at the Berlinale also smashed up his furniture. (A nice, hooligan touch — or a warning?)

Who is this man? And to whom is he, or the film — or its subject — a threat?

Those who follow the international news may recognize the first name as that of, as described by The Washington Post, a “Russian oil tycoon” whose “evolution from ambitious communist to fabulously wealthy capitalist to political renegade has become emblematic of the destiny of post-Soviet Russia.” Khodorkovsky, whose wealth has allegedly funded several Russian political parties and thereby made him a threat to the power of premier Vladimir Putin (or at least an intolerable irritant), had been found guilty of fraud in 2003 and sentenced to eight years in prison, then brought to trial again in 2009 on charges of embezzlement and money laundering and once again found guilty.

Tuschi developed a fascination for the man — “[H]e had more than one chance to leave the country and stay in America with tons of money. Instead he returned to Russia and let them put him in prison. And I thought, why? Even his enemies don’t understand it. This I wanted to explore,” he told ExBerlin. Getting to the heart of the matter, Tuschi told the Berliner Morgenpost that what he mainly wanted to find out was: “Why did such a sharp and strategically thinking man make these mistakes?” And Khodorkovsky was the result. “They’re flipping out in the blogosphere in Russia,” added Tuschi, whose film, Khodorkovsky’s supporters fear, will further damage him. “I just show that [he] is no saint, but a human being.”

That he does. The film is even-handed, offering no judgment on the imprisoned oligarch’s guilt or innocence. And yet, perhaps given the circumstances surrounding its production — “When it came to Khodorkovsky, everyone was afraid,” Tuschi told ExBerlin. “I was afraid, normal people were afraid. Rich people feared losing their money. People in the government feared they would get in trouble” — Tuschi also can’t resist playing investigative reporter. The conceit is not fully realized, however, as his documentarian instincts to let things play out take over and he misses the chance to tease out apparent contradictions in statements of his interview subjects.

What is fully realized, to the viewer’s surprised gratification, is Tuschi’s ability to work his way (not to mention his camera) past innumerable institutional obstacles and interview Khodorkovsky in the courtroom. The interview is as puzzling as it is revealing: Khodorkovsky is charming, relaxed, and utterly self-aware. But then, maybe he knows something. He was, after all, a Putin confidant. How, and why, did everything change? “To me,” Tuschi tells ExBerlin, “the bottom line is: he was better looking and he had more money.” Well, there is more: “He was clean and wanted to become independent, play by market standards. This wish to be really free was the scary thing for Putin.”

What can be a scary thing for someone who is independent, is to awaken from a four-day coma, find yourself in a hospital in a foreign country with no ID, retrace your steps in an attempt to prove your identity — and find that someone else has assumed it so convincingly that even your wife claims that he is ... well ... you. Oh — and find yourself the target of repeated murder attempts. Which also doesn’t ring any bells: As best as you can remember, you are a university professor in Berlin for a biotechnology summit, whose life was saved by the beautiful blonde Bosnian taxi driver who pulled you from the Spree River after the cab plunged spectacularly off a bridge and crashed into the river. Sounds like something out of a movie script.

Which as you’ve probably already guessed, it is; the movie being Jaume Collet-Serra’s blockbuster Unknown, which on opening weekend in the U.S. (also the weekend of its European premiere in Berlin) recouped more than half of its $40 million budget, and by the time this article is posted, will probably have been seen by many, if not most of the people who are reading it. So — let’s go behind the scenes.

For the director, Berlin was the perfect setting for the story. “At the heart of the film is a crisis of identity, and Berlin has that, having been divided for so many years. To me, Berlin was an extension of the main character,” said Collet-Serra. Liam Neeson, who plays the befuddled botanist, felt no such uncertainty when offered the role. “For me, it’s always the script, and this was a real page-turner. My litmus test is this: if I can get to page 50 without stopping for a tea break, then it’s a very good sign. This was such good material that I had to read it all in one sitting.” Producer Joel Silver calls it “a freight train, it just grabs you and goes. And you may think you know where it’s going, but I don’t think you’ll see this one coming.”

The cast and crew probably didn’t see the heavy December-through-February snowfall coming, either, or that the climactic car-chase scene would require 10 nights of shooting in the frigid Berlin air. For Diane Kruger, who plays Gina the Bosnian taxi driver, the scene in which she pulls Neeson out of the underwater car, although filmed in a large tank at the Babelsberg studios, was “very demanding, exhausting,” the strain exacerbated by the fact that she had to spend an entire day fully clothed, thrashing about in the water in a small enclosed space.

Kruger went into more detail about the water scene at the press conference. “I would have been happy to let a very capable stunt lady take over for me, but I felt like in this particular movie, it was very much a part of who Gina was, or is — she’s a pretty tough chick, really — and I felt that it was important that the audience believe that it was me. And even for myself, I wanted to make sure that I believed that I could do this.” Collet-Serra continued the thought, noting that “People don’t realize that if you’re in the water for more than twenty minutes” — “fully clothed,” chimed in Kruger — “ you’re completely exhausted. It’s very complicated. It’s nerve-wracking, it’s dangerous.”

Asked about the film’s Hitchcockian elements, the director was quick to agree, saying that “Hitchcock is always an influence in whatever I do; I’m a big fan.... One of the things that’s very Hitchcockian about the film is the ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances, and there are a few scenes that are an hommage to his movies. He’s definitely a big influence in my work.”

The subtleties of the film and of her character were important to Kruger, who “enjoyed the relationship between Liam’s character and mine. It’s not romantic. So it created a space for two actors to have a complicity and some sort of understanding that is much more honest than ‘huh, he’s hot, she’s hot, let’s help each other out.’ It’s unusual in this kind of film, and I really applaud the studio for allowing us this space.”

Meanwhile, Berlin’s world-famous, five-star Hotel Adlon, where many of the scenes were shot (although the film’s climactic, heart-stopping, glass-shattering explosions were filmed at Studio Babelsberg) was not offended by its portrayal in the film. Still, as a reporter for the Berliner Zeitung noted: “On checking in, the guest is admonished by the front-desk clerk. Despite security precautions every lowlife can slip through the employees entrance. And the security chief is practically an idiot. Welcome to the Hotel Adlon, the most famous guest accommodation in Berlin!”

No problem: Although a few scenes did make them “a bit queasy,” in the end, “We’re figuring on positive international PR,” the hotel’s press arm told the paper. “Everybody knows it’s fiction.” (At the press conference, a Romanian journo invited Collet-Serra to his homeland, where there is “the biggest building in Romania, one of the biggest in Europe: the parliament house,” and suggested it might be ideal for blowing up in a sequel.)

As to the film being fiction, for Diane Kruger, part of it is very real: the question of migrant workers, one that she has encountered in reality in Germany, New York and Paris, each of which she has called home. “And I can well imagine how it is to live in a country where you always have to keep your head down,” she told Tagesspiegel. “How it is to want to survive, although there’s no chance of finding legal work because you don’t have papers. That was something that also interested me about this film, because it gives it a depth and complexity that other action thrillers often lack.”

Cinema purists might go a step further and contend that it is not just action thrillers as a genre but all the things that go with them, characteristics variously found in mainstream cinema as a whole — brilliant color, surround sound, quick cuts, shallow characters — that deprive them of depth and complexity. If so, have I got a film for you.

Hungarian director Béla Tarr, perhaps best known to U.S. auds for 1994's Sátántangó (Devil’s Tango), whose seven-and-a-half-hour screening time made seeing it a challenge in more ways than one, took home the festival’s Jury Grand Prix Silver Bear and the FIPRESCI Competition Prize for The Turin Horse (A torinói ló), a significantly shorter film clocking in at 146 minutes. Tarr’s films have been lauded by such diverse artists as Gus Van Sant, Jim Jarmusch and Susan Sontag, who famously called Sátántangó, “Devastating, enthralling for every minute of its seven hours. I’d be glad to see it every year for the rest of my life.”

For those who fear they may have begun to suffer eyestrain from the vivid hues of Fujifilm and Kodak, or whiplash from the bullet-like rapidity of quick cuts, Tarr’s black-and-white Turin Horse, comprising in all an astonishingly minimalist 30 takes (“I like the continuity [of the long take],” Tarr told Bright Lights Film Journal more than a decade ago, “because you have a special tension. Everybody is much more concentrated”), was either a welcome relief, or cause to regard the cineplex more kindly.

The film was inspired by Tarr’s curiosity about a story he had heard some 20 years before. It introduces the film:

In Turin on 3rd January, 1889, Friedrich Nietzsche steps out of the doorway of number six, Via Carlo Albert. Not far from him, the driver of a hansom cab is having trouble with a stubborn horse. Despite all his urging, the horse refuses to move, whereupon the driver loses his patience and takes his whip to it. Nietzsche comes up to the throng and puts an end to the brutal scene, throwing his arms around the horse’s neck, sobbing. His landlord takes him home, he lies motionless and silent for two days on a divan until he mutters the obligatory last words, and lives for another ten years, silent and demented, cared for by his mother and sisters. We do not know what happened to the horse.

Bela Tarr and his Silver Bear for Turin Horse. (Photo from the Berlin International Film Festival website).

This introduction is, to return to Hitchcock, something of a McGuffin: Tarr’s film is concerned not so much with what happened to the horse, but rather with the conditions surrounding the episode that, at least apocryphally, drove Nietzsche mad. (It may not end with Nietzsche: The film’s deliberate pacing caused Screen International to suggest that it “ought perhaps to be accompanied by a warning for the depressive.”) At the press conference, Tarr was faced with a small group of journos who seemed determined to unlock the mysteries of the small, soft-spoken, gray-haired man before them, and it almost seemed, for a few — if they asked the right questions — perhaps even those of life itself.

Watching your film, I couldn’t help but think of Samuel Beckett. Is there still too much hope in this world? Tarr gave it some thought. “We don’t want to convey hope, we don’t need to come up with a solution, it’s not our job to do that, or to tell people what they should do next, what direction they should be moving in,” he said at last “We can simply report, simply depict, simply narrate. To show the way in which we see the world, what happens. And I think this film shows what happens sooner or later to every one of us: transience. The fact that everything in the world passes away is very important. Perhaps the world itself,” he concluded quietly, “will pass away.”

How does it feel to have your film competing at the Berlin Film Festival? Tarr didn’t bite. “It’s very strange to have works of art competing against one another. How do you compare Proust to Dostoevski? You see how absurd the question is. The question is whether a film is authentic, whether it’s true, whether it moves people and touches them. I think everything else is completely irrelevant.

“In two weeks’ time everyone [will have] forgotten these prizes. The next festival keeps rolling along, new films keep rolling along, more glitter. It’s simply not worth it to get involved in this kind of combat; we lose our authenticity.”

Will this be, as rumored, his last film? Tarr declined to answer the question directly, allowing only that “With this film we’ve come full circle, and after this point perhaps we’d end up repeating ourselves.” Co-Director Agnès Hranitzky pointed out that with Sátántangó, film itself was said by some to have reached its apotheosis. Now, “With this film we’ve abolished film. We’ve brought film to its logical conclusion.” (A sobering thought for the talents.)

Each of your films seems to end on a note of hopelessness. And yet you come back and start again. How do you manage to start again? “We get up in the morning and look in the mirror — some people don’t even have a mirror, they don’t have a roof over their head — but each and every one of us gets up in the morning and starts the day new, over and over again. There’s this pathological clinging to life, this pathological insistence. How miserably we live, but nonetheless we want to experience that day, and the next day.

“Because we always think that something’s going to happen on that day, things can’t go on like this, something has to happen. And if this sense of revolt awakens in people, then it’s worthwhile after all. And perhaps things will turn out all right.”

But Tarr is clearly of two minds on that score. “The film portrays mortality,” he writes in his Director’s Notes, “with that deep pain which we, who are under sentence if death, all feel.” Tarr’s despondency may have its roots, at least in part, in the current political situation in his homeland, which the director spoke of in an interview with Tagesspiegel. “For the past 20 years Hungary was free, but now, once again, that’s over. A horrible déjà vu.” A group of prominent Hungarian artists protested against the ruling nationalist party’s draconian actions — “The government cut off every subsidy. Half of all producers are already broke. Cinemas shut down, even my own production plans are on ice, although everything is ready with my financial partners” — and were soon joined by 40 international artists.

Are you playing with the idea of moving, going abroad? “I am a Hungarian. This government has already changed the constitution, and is preparing for a 20-year stay in office. But they have to go. Not I.”

Leaving one’s homeland, and in some cases even one’s hometown, is a radical decision that few undertake without a compelling reason. And few reasons are as compelling as the one facing a loyal young party official who learns, by chance, of the explosion of a reactor tower in the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. But the Party bosses around him are denying that anything happened and warning him not to spread needless panic, while his girlfriend only half believes him and insists on buying a new pair of shoes when her heel breaks in their rush to the train station. And, after all, it’s Saturday, people are out enjoying a beautiful spring day, there’s a wedding going on, everything seems normal. Besides, the band needs a drummer after theirs succumbs to one too many vodkas, and Valery used to play percussion with them...

Alexander Mindadze’s Innocent Saturday (V Subbotu) is an intensely wrought dramatic imagining, or in the director’s words, “filmic metaphor,” of the Chernobyl catastrophe. “What really fascinated me was the question as to why people who knew about the catastrophe did NOT escape the city. Perhaps because the danger was invisible? For people who live unreflectingly, obliviously, who are satisfied with their everyday lives — for them it is the many little pleasant aspects of life that become increasingly valuable in such circumstances,” writes Mindadze. “When life has become intolerable and is reaching its end, it blossoms one last time before it vanishes...”

At the press conference the director, who also wrote the script, asserted that Chernobyl is “still with” the Russian people. “It’s genetically embodied in us now and will be in the future,” but at the same time “paradoxically, life was flourishing in that time of imminent danger.”

The film’s German producer noted that although they tried to remain apolitical, the film is nonetheless inescapably political “in two respects: in the sense of the ‘big lie,’ of people hiding the disaster, which may be a systemic fault of the system”: it would turn out that the people were not officially informed until 36 hours later. “And I think it also may have contributed to the fall of Gorbachev.” The film’s Russian producer called Chernobyl “not just an important event which killed hundreds of thousands of people [immediately and for years afterward], but it was one of the major reasons that broke up the [Soviet empire], because when Gorbachev made his speech on the eighteenth day of the tragedy, when millions of people came out on the streets, the drama of silence, the ‘big lie’ as was already said,” made him think of doing a movie about it. But none of the scripts he saw sold him like Mindadze’s.

For his part, Mindadze told us that his “expectations have been met” by having the chance to meet the press at the Berlin Film Festival. “The more people that will see it, the better it is for us. That’s what we work for — the producers, the actors, all of us.” Added another of the producers: “Ever since it happened, the root causes of this disaster have not been [publicly] identified, and it’s the most severe technical disaster in history.... We felt it very important to show it here at the Berlinale on such a high level because we believe that it’s something the media should continue to talk about.”

What was the young actors’ familiarity with the disaster before making the movie? While Anton Shagin (Valery) mainly recalled the different-colored meal coupons children “with certain dietary requirements” got in school because “they were in the epicenter when the disaster happened,” Svetlana Smirnova-Marcinkevich, who plays his girlfriend Vera, was in her mother’s womb at the time, “and everybody was very worried, they were giving toys and clothes to people living in that area.” The film’s costume designer, she recalled, who was an adult and was there, told her that “‘people really weren’t very worried at all ... It was only a day after the disaster that they were told something had happened, and they were taken out of the city, never to return.’ When she told me that, it really made my flesh creep.”

Critical reaction to the film was interesting, in at least two cases, for the way in which the writers’ personal point of view clearly influenced their assessment. For the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (FAZ), Innocent Saturday “could have been a big film ... Unfortunately, it wound up being just a small film with big ideas.” The writer was disappointed by the director’s decision to “throw away the tension he’s built up in the first minutes on narrative gesticulation, plot ‘noise,’” concluding that “the film thereby loses its force.” He clearly had been prepared to like the film — lavishing six column inches on a respectful deconstruction of the action of those “first minutes” — but then recalls a Munich revolutionary’s slogan: “We’re all just dead people on vacation,” and faults the rest of the film for not just taking it literally but also proceeding to show the inconsequentiality of their last minutes in equally meaningless detail.

For Neues Deutschland, whose critic was a student in Kiev during the summer of 1989, maybe we shouldn’t be so quick to condemn the inaction of others: “Is it always other people who shut their eyes in the face of danger? In the summer of 1989 ... everyone had known for a long time the scale of the radioactive contamination.... It was a beautiful summer and I went swimming every day in the Dnieper River. Why this irrationality? Because everybody was doing it and you’d rather believe in normality than in a [constant] state of emergency.” (We can only hope that few, if any, in the center of Japan’s ever-worsening nuclear crisis are caught up in the same state of denial.)

The Berliner Morgenpost critic also took it personally, but in a different way: Watching doomed people party like it’s no tomorrow “is hard to bear, because you want to kick Valery in the butt.... [The characters’] inability to flee is also a kind of martyrdom for the viewer because it’s incomprehensible. They remain in the death zone and live for the moment. Cheers! They drink a vodka. And then some red wine.” Concludes the critic, understandably feeling somewhat benumbed: “I’ll have a schnapps.”

A far more dangerous forgetfulness drug — one that has increasingly been of concern to parents of teens and caused more ink to be spilled, in everything from advice columns to medical journals, than an overturned “hp” truck — is the Internet. Specifically, the virtual world that allows many to escape the sometimes threatening outside world for the seeming security of one where, at least at first, they feel secure and in control. But the virtual world can be equally dangerous, as the young victims of vicious cyber-bullying have learned. And as the world has learned, by reading their heart-rending stories.

Twenty-nine-year-old Polish director Jan Komasa’s Suicide Room (Sala samobójców) brings to the screen with heart-stopping CGI that alternately grabs you out of your seat and thrusts you back into it, the story of a spoiled upper-middle-class teen with preoccupied professional parents who becomes one of those victims. Dominik makes the fatal mistake of taking a dare at his prom party to make out with one of his male friends. Of course, the kiss is captured on somebody’s cell phone and posted on the Web for all to see — and for some to see as an opportunity to make Dominik’s life a living hell.

Unable to talk to his parents (“Even if you are gay, keep it to yourself”) and receiving about as much support from his teachers, the boy shuts himself in his room and finds what he thinks is solace online with the dark and mysterious Sylvia. But his savior turns out to be more satanic than angelic, eventually revealing herself as the Queen of the Suicide Room whose faithful stooges are spectral, bone-chilling, bloodthirsty avatars straight out of Sword & Sorcery.

At the press conference, the director (who could pass for a high-school kid himself) explained that when it came to the animation, “The main thing was to direct avatars,” beginning with animatics to see what worked, then shooting the scenes with real actors “using multiple cameras,” and handing the edited results over to the animators “so they could reconstruct it in the 3D world. We did not want to hide that we’re in a game” by using a “photorealistic shoot like in Avatar by James Cameron,” but instead wanted to make it look like a 3D game “and become more and more realistic” — what DP Radoslaw Ladczuk called “stylish animation.” “You see the avatars breathing, we hear their screams of pain,” continued Komasa. The “main issue” was to have the actors’ gestures “transferred into the 3D world.”

While the actors spent months observing high school students to get their behaviors down, the director was also inspired by the classics. “The movie is very contemporary, it’s now, it’s modern, it’s in reality. So maybe that’s why we went to literature to find role models,” deciding to use Goethe’s Werther and Shakespeare’s Hamlet as role models for Dominik and the world surrounding him, reading them through and studying them carefully as they developed “his attitudes, his approach to reality.”

As for Sylvia, “we wanted to use the language of poetry” in creating her, said Roma Gasiorowska, who plays her in the film. An important element for Gasiorowska was that the animated world was more meaningful, more real to Dominik than the “real” world, where people were more one-dimensional than the avatars he came to know.

One of Komasa’s inspirations was an article about a teenage girl who had committed suicide, whose mother he interviewed, then gave the script for feedback. She expressed concern that Dominik’s parents were portrayed as heartless and selfish and questioned that as simplistic, even off the mark. “So we ‘de-monsterized’ the parents,” instead making them “lost.”

“In a world where everyone has learned how to express one’s needs and fight for oneself, to be effective and demanding, everyone knows how to speak,” writes Komasa. “However, not everyone knows how to listen.... Suicide Room is a hymn for suicides, all those who kill themselves every day, a hymn about stopping for just a short while and listening, since this could let one live for at least a second longer.”

We get up in the morning and look in the mirror — some people don’t even have a mirror, they don’t have a roof over their head — but each and every one of us gets up in the morning and starts the day new, over and over again. There’s this pathological clinging to life, this pathological insistence. How miserably we live, but nonetheless we want to experience that day, and the next day.

Because we always think that something’s going to happen on that day, things can’t go on like this, something has to happen. And if this sense of revolt awakens in people, then it’s worthwhile after all. And perhaps things will turn out all right.

When that “sense of revolt awakens” in people who decide that “something’s going to happen” because they’re going to make it happen, whether “things ... turn out all right” depends in large part on who they are, what drives them, and what they’re willing to do, and risk, to achieve it. If Not Us, Who (Wenn nicht uns wer), award-winning German documentarian Andreas Veiel’s first feature film, brings to the screen the politically and emotionally explosive story of the ménage à trois between Gudrun Ensslin, one of the founders of the German terrorist Red Army Faction (RAF); Bernward Vesper, son of an unrepentant Nazi, whose interest in revolutionary literature she shares; and Andreas Baader, for whom she leaves Vesper to form what later came to be known as the Baader-Meinhof Group. (Journalist Ulrike Meinhof was a friend of Ensslin’s who helped break Baader out of prison.)

DC filmgoers are probably most familiar with Gudrun Ensslin and Andreas Baader by way of Uli Edel’s Oscar-nominated The Baader-Meinhof Complex (2008), in which Bernward Vesper doesn’t even merit a mention, no doubt because the film focused on the political and ideological extremism motivating the group’s acts of terrorism. Veiel, on the other hand, had a motivation of his own. Its source was Gerd Koenen’s “Vesper, Ensslin, Baader — Urszenen des deutschen Terrorismus [Prehistory of German Terrorism]” which cast an entirely new light on what preceded the events that would shake Western Europe in 1968 and would have far-reaching repercussions around the globe. “I realized after the first few pages,” said Veiel, whose 2001 documentary Black Box Germany had already examined the relationship between Ensslin and Vesper, “that what seemed so ‘already told’ was new and fresh here.”

At the press conference, Veiel agreed that his film and its title have contemporary resonance. “We have problems in this world from the next climate disaster to the next financial crisis. We still have to get involved today. That’s why the motto ‘If not us, who?’ is still valid today.” (As was the Berliner Morgenpost’s variation on the theme: “If not him, who?” a reference to Dieter Kosslick’s rumored departure from Berlinale chiefdom after this, his tenth year at the helm of Germany’s biggest film festival. Another headline called Kosslick “The man with a victor’s smile,” while The Hollywood Reporter labeled Berlin “Europe’s new It city ... the place to be.” Why leave indeed?)

In an interview with Screen Daily, Veiel dismissed the contention of those who reject the combination of a love story with a political story as the equivalent of “sprinkling sugar on it. In this case, it is bullshit. If you go into these political issues, you cannot ignore the personal side of the protagonists, because the love story is the nuclear fusion behind it.” Veiel’s fusion lit a spark: The film won both the Alfred Bauer Prize in memory of the Berlinale’s founder for a work of particular innovation, and the Prize of the German Art House Cinemas.

In a press interview, Veiel said he felt more constrained when making feature films, a feeling some might associate more with the making of documentaries. Not Veiel. “Documentary work allows me to tell a story with more complexity. In purely fictional works my hands are tied by dramaturgical needs and emotional undertones. That can be stretched, but if it were about the complexity of a finance system, bringing a love story into the mix would be absurd. Structures are in one playing field; love stories are in another.”

Interestingly, Veiel’s next venture, according to Variety, will be a film examining the financial crisis, which given his remarks we can assume will be a documentary. That is not to say, however, that other filmmakers might not see the possibility of finding humanity, and even love, amidst the complexities of the financial system, as J.C. Chandor did in Margin Call (above). Or for that matter, that fictional films are guaranteed purveyors of drama and emotion.

In Nanouk Leopold’s Brownian Movement (Netherlands/Germany/Belgium 2010), Sandra Hüller — whose bravura performance as an epileptic university student who begins to believe she’s possessed by demons in 2006's Requiem earned her nine international Best Actress awards — plays a physician driven by her own equally persistent, and equally inexplicable, inner demons.

In contrast to the theme, the film itself is handsomely, deliberately, coolly shot, which either intrigued, bored or annoyed critics. In one scene, when Charlotte’s handsome, successful husband (with whom she has what seems a loving relationship) discovers the truth of her “extracurricular activities” — she’s even rented an apartment for her purely physical, utterly emotionless sexual encounters with patients chosen because they have something physically repugnant about them — the two of them sit, expressionless, on the bed, each staring blankly ahead, for a full five minutes.

A critic for mubi.com praised Hüller’s “tremendous performance as clinically precise in its introspected abstraction ... as the film is aesthetically so,” while dismissing the film as a whole as “art cinema ... and one of pregnant silences and empty interiors amply decorated.” Indiewire, on the other hand, found it “emotionally affecting and troubling,” crediting Hüller’s “transfixing and courageous performance,” while The Hollywood Reporter split the difference, saying the film “squanders its noteworthy features on a story that’s slim to the point of emaciation.” The Berliner Morgenpost lamented that “It is not for one second about empathy and psychology, which are part of every good melodrama, just laboratory tests.”

For Hüller it was a dream role that she wanted as soon as she read the script, the actress told the Berliner Morgenpost in a separate interview. “There are characters I must play because I don’t want anyone else to play them. That mean so much me that I must protect them.” As a policy she neither pathologizes nor psychologizes her characters, the actress noted, but rather approaches them from a basic idea, which for Brownian Movement was a universal, almost biblical love outside the bounds of convention. This woman feels herself connected to everyone, said Hüller; these were much more than mere sexual encounters. “For me there was nothing dirty or forbidden in it.” Of particular interest for the actress was what, if anything, the role had to do with her and her own life. “Do I really fall in love with other people, or rather, with the picture I have of them? Or does it just fill an emptiness in my life? I find that fascinating.”

And then there is the love that Leopold’s camera has, per the Tageszeitung, for Hüller’s face. “Yes, you can say everything,” the director told the paper in explaining her disinterest in verbal exchanges. But for her, the body, the face and the eyes are the most reliable storytellers, here closely examined by the camera’s long-held close-ups and extreme close-ups. “My characters must always ask themselves: ‘How much can I bear to know about myself?’”

A question that director, actor, screenwriter, author, visual artist and performance artist Miranda July, who burst onto the cinema scene with 2005's Me and You and Everyone We Know (it took four prizes at Cannes and a special jury award at Sundance) and has not let the flares fizzle ever since, asks in The Future, one of Kosslick’s favorites this year according to the Berliner Morgenpost. Which must be true: it had eight screenings (including two invitation-only for the European Film Market), a rarity at a festival with more than four hundred titles.

But back to the question of self-knowledge. “In a moment of desperation,” we read in the film’s press book, “[Sophie] calls a stranger, Marshall — a square, fifty-year-old man who lives in the Valley. In his suburban world she doesn’t have to be herself; as long as she stays there, she’ll never have to try (and fail) again.” Or live up to her boyfriend’s, or her own, expectations.

It all begins with a stray cat that Jason (Hamish Linklater) and Sophie (July) have found and decide to adopt — they name it PawPaw — but it needs medical work. Reluctantly, they leave it at the animal shelter for treatment for what they are told will be a month. The cat becomes the film’s narrator in the form of a cartoon character, voiced by July in a gentle, meowing tone, who expresses their unarticulated thoughts and feelings, along with those of the hopeful stray who lives in anticipation of their return. But PawPaw will not survive. And neither will their love.

At the press conference July was asked why she decided to use the cat as a narrative device. “I think it’s hard to talk about longing and love in a new way, because we’re so used to talking about it in the same way, and even maybe feeling it in the same way. And so I had to find [a place] to put love and loss that was new to me so that I could feel it new. And so, maybe,” she added, looking out across the packed press room, “you guys could, too.”

Your film is also about the life in the cage and in the wilderness. Could you tell us a little bit about that? “The wildlife — the desires you have despite yourself that maybe aren’t even the best idea — and also the fears,” responded July. “I mean, during the day [maybe] you can believe in all this. But at night, maybe even all the things you hold dearest don’t even exist. And to me, that’s the true wilderness.”

In the part where Sophie tries to dance and can’t: Have you ever gone through a similar situation with your work? “One of the greatest possible villains in my life is, “‘What if I couldn’t make art?’ And it feels like I just might have to abandon myself. And if I did that, what would I do? And so I followed that nightmare to the end. Which is almost like a fear fantasy. In real life, luckily I have a little bit of Jason in me. And he’s very filled with faith, and he’s curious. On a good day, that’s really all you need. Just a little bit of that.”

Asked how she found her actors, July was unequivocal in her esteem for them and for her casting director. “When you’re casting these intimate men, it’s like an opportunity — you can have anyone,” she murmured with a flirtatious shrug and eyeroll, causing a ripple of appreciative laughter in the audience. She then grew serious, declaring that her casting director had proved prescient when she put these two actors at the top of the list: After dutifully auditioning dozens of aspiring Jasons and Marshalls, July had to admit that the first were indeed the best. Asked what it was like to work with July, both the thirtyish Linklater and the fiftyish David Warshofsky (who plays Marshall) briefly became tongue-tied and even seemed to blush almost imperceptibly, finally praising her to the skies.

“This beautiful script ... it’s a beautiful read, and Miranda’s vision is so laser-sharp and clear,” said Linklater. “She’s really special, so I was really lucky.” Warshofsky described the “odd experience” of having one person in three roles: “You’re acting with somebody — and they wrote the words — and then they’re also directing you. So every time you have a question, you’re going to the same person.” Warshofsky concurred with Linklater’s appraisal of the script, adding that “Miranda and I would sometimes even say, ‘We have to trust the script.’ She’s the one directing me, she’s opposite me, and she wrote the script. And we’re saying ‘We have to trust these words. They will save us.’ It was,” he concluded, “a miraculous experience.”

But that’s OK; even the press was smitten. “An elfin creature has evaporated into the ostentatious, taste-hostile lobby of a Berlin hotel,” wrote an awed Tagesspiegel reporter, “a Puck, a Pinocchio, a marionette-made-human of her own imagining.... The large eyes are fixed on the stranger, and — watch out! — he who gazes into them a second too long, drowns in a fairy lake!”

Which, all things considered, is not a bad way for a film critic to go. Certainly better than drowning in a desert full of weeds, which is what Argentinian filmmaker Rodrigo Moreno sees as the purpose of his work. “At first glance, it can seem boring and unattractive, but that’s what I like in the world.” On the other hand, part of Moreno may find a kindred spirit in July: “I’m not interested in winners and losers. I’m interested in characters who are outside of the competition.”

A Mysterious World’s (Mundo misterioso) Boris is not only out of the competition; he’s utterly out of gas, both literally and figuratively: The incongruously colored baby-blue, Ceaucescu-era Romanian rattletrap the expressionless Boris buys breaks down, shortly after his relationship with his (equally blasé) girlfriend — whom we meet in a static, 10-minute bedroom scene shot canted and sideways, forcing us to stare at the least expressive parts of their heads — does the same. (“In the audience a man groans in pain,” observed the Berliner Morgenpost, “as though he’s got 1,000 hours of relationship dialogue behind him and really doesn’t need any more of it in the movies.”) Linklater set the gold standard for slacker movies (if that’s not an oxymoronic concept); it would take more than this to challenge, or even to approach him.

But there are some saving graces, including effective atmospherics in a scene where Boris is driving his car in a thundering downpour: seen from his POV, his face sporadically illuminated by the headlights of passing cars as they zoom by, an intense sensation of claustrophobia sets in, and you can almost feel and smell the rain. Or the scene where Boris takes his car to the mechanic’s shop: Here, the meticulous deliberateness with which the older man examines the engine, analyzing it aloud as he slowly lifts, shakes or twists each part, identifying them as though he expects Boris to remember — even the way he languidly prepares and stirs his tea, to Boris’s frustration, before commencing the repair — is spellbinding.

At the end of the film there is a surprisingly affecting song, “Déjà.” Surprising, because the viewer has not really built up any emotional investment in the film, or anyone in it. Yet the song, recorded in 1931 by iconic Argentinian tango singer Carlos Gardel, hits home. “Rain has a destiny that I would like to have,” sings the guitarist. “How nice my destiny would be if I could run along the path to kiss the thirsty stones and flow between the stones, then go back up to the clouds and become rain again.”

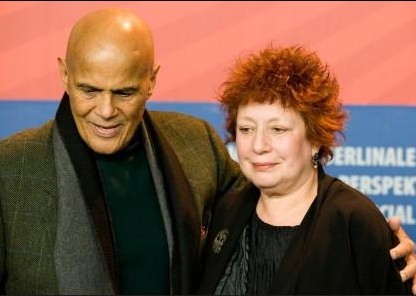

Few have achieved that renewal as affectingly — and effectively — as the subject of Susanne Rostock’s rousing, inspiring biographical documentary, Sing Your Song, which opened this year’s Sundance Film Festival and had its European premiere at the Berlinale, its star the toast of the town. “B is for Belafonte, Harry,” according to the Tagesspiegel’s “festival alphabet.” Why? “Was celebrated and surprised with a prize [the Berlinale Camera] at the Freidrichsstadtpalast on Sunday, attended the Talent Campus on Monday, [received] the UNICEF Germany Honorary Award [for Child Rights] at the Academy of Arts on Tuesday, and on Wednesday [returned] to debate the revolution in Egypt. And the man,” it concluded, “is almost 84!”

Sing Your Song: Harry Belafonte and Director Susanne Rostock. (Photo from the Berlin International Film Festival website).

Indeed he is. But Harry Belafonte’s youthful vigor and fifty-plus-year commitment to what began as civil rights, expanded to children’s rights and now encompasses global human rights would put Bono (who, after all, has only been on the earth for as long as Belafonte has been a fiercely impassioned activist) to shame.

In short, it’s way past time to draw the shades on “Day-o.” And yet ... in a larger sense, maybe not.

As we see in the film, distilled from over 70 hours of interviews, eyewitness accounts, movie clips, film and TV footage, and excerpts from FBI files, what may at first glance seem demeaning — reducing a man who is not only a singer, but an actor, composer, author, producer, and lifelong activist who is very much in the now — to a song from 1956, may not be, when viewed from another angle. Especially when that angle comes in the form of advice offered by a fellow African American singer, actor, and civil rights activist: Paul Robeson.

The young Belafonte was performing at a club in New York, he related, when Robeson came to see him backstage. “Get them to sing your song,” the older man told him, “and they will want to know who you are. And if they want to know who you are, you’ve gained the first step in bringing truth and insight that might help people get through this rather difficult world.”

Belafonte brought them both to the Hyatt hotel after the press screening, answering questions with unfailing graciousness spiced with frankness and humor. This being Germany, the first question dealt with his previous appearances in that country. When was your last concert in Hamburg? After much back and forth on possible dates with his producers onstage and his associates in the audience, Belafonte looked out at us and smiled ruefully. “I have four promoters — they’ve represented me for 30 years — and they’ve all lost their memory,” he finally said, to appreciative chuckles.

Not so Belafonte, whose memory on more critical matters was all too sharp. Asked by a reporter from African Refugee News with a quiet hopefulness tinged with a sense of inevitability and despair what can be done to stem the tide of violence in Africa, Belafonte turned serious, looking down at the podium for several seconds as pain crossed his face. “When I was younger — like you,” he finally said with a smile to the late-middle-aged reporter, “I thought all things were possible. And that all you had to do was do it once, or maybe twice, and all things would be perfect. Now that I am a little bit older — I’m not too sure how much wiser — I’ve just found that the [peculiarities] of the human [species] are forever giving us surprises.”

His spoke slowly, choosing each word with great care, accelerating at moments that clearly meant a lot to him or using his hands for emphasis. “I have no idea how long anything will take. It seems each time we fix something we wake up the next day only to find there’s yet more to be fixed. I think those who resist progress, those who resist truth, work at that scheme 24 hours a day. I think people who are activists and get involved in ‘decent’ deeds take time off, and rest, and think. It’s during those periods of ‘blinking,’ I think, that we sometimes lose our vision or our path.

“In my film I have a conversation with Nelson Mandela, and I asked him pretty much the same question you just raised. And he said, ‘I don’t know. Just keep doing it. Keep trying.’ I had never suspected that there would be a Tunisia. And then a Yemen. And then an Egypt. I have no idea where it will next come from.

“What encourages me is that I think the globe is finally in motion. And with the use of technology, and all of the things that are at our disposal, people are beginning to discover each other in ways that they have never discovered each other before. And I think what we see in that ... is progress.” Belafonte cautioned the West not to be “too quick” to brush off the populist uprisings in Africa and the Middle East, reminding us of the national impact of a black woman whose refusal to move to the back of the bus became a catalyst for the U.S. civil rights movement.

Expressing great respect for the intellectual capacity of John Kennedy, Belafonte said that he sees Barack Obama as the next in line, “one of the most intelligent presidents we’ve had in a very long time,” one who “is learning. He may be learning a bit too slowly” — an observation that was greeted with knowing chuckles from the audience — “but he’s learning.” What he lacks, said Belafonte, is “an active community, an active citizenry” to be a driving force such as there was in the sixties. “That’s the only ingredient lacking in America: There’s no force ‘pushing’ Barack Obama. The only voice he hears is the one percent, Wall Street, that carelessly and recklessly shape the economy to serve them only.”

But other voices are out there, and Belafonte and his daughter Gina (“who can sometimes be a royal pain in the ass — ”), producer of the film and every bit her father’s daughter (“He taught me everything I know,” was her swift reply, causing him to add: “— and I love her forever”), have harnessed those of young people, gathered together several years ago under the auspices of “The Elders,” civil rights activists and supporters of the elder Belafonte’s generation. Their purpose? To explore what concrete steps could be taken to address the high rate of youth incarceration, with a focus on African-American youth, in the U.S. [Since the first “Gathering for Justice,” The Gathering has grown into a nationwide organization of 48 groups. Its focus has expanded to include a range of social justice activities.]

Belafonte was “absolutely delighted” to have the film invited by the Berlinale, as it took him back not only to those concerts of so many years ago — coming back to Germany is “the most poetic thing that could happen” — but even earlier, to his drama student days, when he and Marlon Brando (“we were very close”) shared the same German drama teacher, a Max Reinhardt specialist. It was Brando’s passing in 2004 that was the impetus for Belafonte to make a film that would capture the people whose courageous actions, he felt, should not die with them (as he feared Brando’s had), and Gina’s urging that turned it into a film about Belafonte: his life, his remarkable history, his still-propulsive passions. The film is scheduled to air on HBO this fall.

Across the ocean, meanwhile, the Oscars were less than two weeks away, and The New York Times’s Manohla Dargis and A.O. Scott were wondering whether in the “Age of Obama,” Hollywood may have “slid back into its old, timid ways” and stopped making meaningful films about black people. “Is class the new race?” they asked.

Ah, the Oscars, in whose glitter Berlin basked well ahead of the game. True Grit? For the press conference of the festival’s opening film, the Coens came fully loaded: Bridges, Brolin and Steinfeld. The King’s Speech? His Majesty himself graced the stage, crowned with a new title: “Colin the Firth,” inventively anointed by (as it would turn out) several scribes. And a flick featuring filmdom royalty and a playbook borrowed from the Bard: Coriolanus, set to singe U.S. screens (Variety called it “bloody” and “bellicose”) later this year, brought Butler, Fiennes and Redgrave before the maw of the international press.

Berlin loved Joel and Ethan Coen, their film and its stars, on a gut level if not always an aesthetic one. Most of all the local press loved interviewing not only the film’s stars but its director brothers, who while superficially similar in appearance (both are dark-haired and bearded with glasses), could not be more different in demeanor, with Joel a cross between aging hippie and biblical scholar and Ethan more the affable guy next door. The indisputable favorites at the press conference were more firmly on either side of the age and experience divide. Jeff “Rooster Cogburn” Bridges, whose 60-year screen career is at one with his age, grew up in the business and was held in his mother’s arms before a movie camera at the age of four months. Conversely, Hailee “Mattie Ross” Steinfeld’s entire résumé is — or was, at the time of the screening; there will no doubt soon be several more notches on her actor belt — seven lines long.

What was the most difficult challenge for you in making this film?, came the question for the delightfully self-possessed Steinfeld, who tried to come up with something before admitting that “once I got the dialogue down, I didn’t really have anything to worry about after that.” She turned to see if Joel could come up with anything, but he could only agree. “We told her, ‘You’re gonna have to go down in a cold river and after that be hangin’ out of a tree, you know, 60 feet off the ground,’ and she was like, ‘Yeah, OK, fine,’” he said, mimicking her pleasantly equable shrug. [“She definitely understands she’s driving the truck, the truck being the expedition,” Ethan told The Hollywood Reporter. “That’s the central joke of the book: she’s the grownup.”]

Why do you think this film is the biggest success you’ve ever had? With neither of the brothers willing to bite, Jeff Bridges replied. “I think it’s maybe that people are finally becoming hip to how great the Coen brothers are. They are masters. They make it look so easy , but ... That’s my theory, anyway.” (Asked by the Berliner Morgenpost what his reaction was when the Coen brothers offered him the script, Bridges minced no words: “That the gentlemen — and many will say this is no new discovery — were stark raving mad,” because True Grit was “a classic of the genre” for which “the legendary John Wayne” received his only Oscar.)

Why is there so much violence in your films? Does it stem from something within you, or something else? Ethan shook his head. “The violence thing I tell you, I find it hard to relate to myself; you know, it’s not a personal thing,” he said, but “when you tell a compelling story, you want the stakes to be high.”

And the dialogue: It’s almost biblical in its complexity. How did the actors deal with that? Bridges took his cues from the book, but agreed that it was “a challenge getting your tongue around” the “lack of contractions” in the language and apologized for the “intelligibility” of some of his dialogue. “But that’s the way the guy talked, and you want to be consistent to that and still be understood. Fortunately we have subtitles. Even in the English version,” he cracked, to uncertain laughter from those who had not yet seen it.

As to why they decided to do a “remake” of the classic John Wayne film, Ethan made it clear that while they had seen the original film as kids, they had only vague memories of it and instead drew their inspiration from Charles Portis’s novel (on which the earlier film was also based). The point was emphasized to interviewers by the brothers and Bridges whenever they were asked what became the inevitable question. (When offered the role of Rooster he asked much the same question, Bridges told us, and was told to read the book. “And I was surprised at how it read like a Coen brothers screenplay!”) A key difference is the POV: Like the book, the Coen brothers’ film is told from Mattie’s.

Speaking of which: What was it like to be the only girl among all those guys? Josh Brolin cut in with a rakish grin: “This is more about you, isn’t it?” he teasingly prodded the woman journalist. “It’s more about you than about Hailee,” then leaned over to give Steinfeld an affectionate squeeze. After saying how great the guys were to work with — “they all really became father figures to me” — Steinfeld noted that she was actually “surrounded by women the whole time,” including her mother and much of the crew. “Actually, she kept us all in line” with a “cursing cup,” said Bridges, recalling how much she charged for “the s-word” or “the f-word.” “She made much more money from that jar than she did from the movie,” smiled Brolin ruefully.

In an interview with Berliner Zeitung, Bridges became philosophical. Do you like playing typically American characters? “Dunno. Nobody asks a fish how it feels to swim in the sea. American culture is all I know.” Do you see yourself as an American antihero, someone who in True Grit conquers the West practically against his will? “The whole human race is antihero. We’re hopeless bunglers, complete wrecks, and for whatever strange reason are still allowed to exist on this earth. That’s a real miracle, isn’t it?”

Not that we always make it easy for each other to exist on this earth, especially those in insular, repressive societies who dare to challenge centuries-old social, moral and religious codes that both define, and sometimes threaten to destroy them. In the CICAE- (Confédération Internationale des Cinémas d’Art et d’Essai, or Confederation of Experimental and Arthouse Cinemas) winning The Forgiveness of Blood, which also won the Silver Bear for Best Screenplay, director Joshua Marston and his Albanian-born co-screenwriter Andamion Murataj draw us into a country that, although a member of NATO since 2009, has remained resistant to some of the social and cultural changes that have spread throughout Eastern Europe since the fall of the Wall. But only some.

The film opens somewhere in Northern Albania,. Two men in a horse-drawn cart crossing a field of mostly dead grass come across several large rocks blocking their path, wearily remove them, and continue on their way. Cut to a group of teens chatting on their cell phones, sending SMS messages and planning their weekend in what seems to be the universal teen argot — except it’s in Albanian. In every other way it could be any U.S. city: one of them takes a funny photo of some of the others with her phone, they all agree it’s awesome and decide to upload it to Facebook. Even at home, parents and their video-game-hooked kids have the same conversations found in any middle-class home. So — having forgotten the horse-drawn cart, which now seems like something from another film — we are totally unprepared for what happens next.

It seems that by removing the stones and taking the familiar route they and their family have taken for generations, Mark and his 17-year-old son Nik have trespassed on what their hotheaded neighbor insists is now his property. The neighbor approaches the cart in a fit of righteous anger (he did, it turns out, purchase the land) and nastily insults both Mark and his manhood. The spark will ignite a blood feud based on an authority even more ancient than Mark’s claim. One that demands retribution not against the father, who has gone into hiding for fear of his life, but in his absence, against one to whom it is almost as foreign — “In our European world there is no place for fights over honor that draw blood and reduce life to the principles of an archaic code,” observed OutNow in its review — as it is to 21st-century Americans. (It would not have been to Rooster Cogburn.)

Nik feels himself very much a part of that European world. And that his father’s rash act could mean the boy’s virtual imprisonment in their small home, because the traditional laws that guide, and can even dictate behavior give the neighbor’s family the legal right to exact eye-for-an-eye vengeance upon the eldest son ... is like virtual reality gone horrifyingly real. And yet, in this time that is so woefully out of joint, where a woman’s place in a fiercely patriarchal society is ruthlessly circumscribed, it is his younger sister who, finding herself the only member of the family whose movements are not restricted, will find the strength to keep the family itself, anchored for centuries at least nominally in its men, from going under.

At the press conference one of the journalists remarked that, given that the film ends with the face of the young girl, “it looks like the future of Albania lies in the hands of women,” who throughout it “seem to be cleverer, stronger, and do not think only about themselves.” The actress who played the role responded forcefully, emphasizing that it was the importance of family and their well-being that moved her character to react as she did. “Any Albanian girl would do the same,” she declared.

Director Joshua Marston summarized the conundrum confronting the NGOs that are trying to help Albanian society free itself from the destructive elements of the Kanun: If the government pays the “elders” who interpret Kanun law and issue judgments, it is in effect legitimizing that which the state wishes to phase out and eventually do away with. If, however, the government doesn’t pay them, it is then left to each family to come up with large sums of money, without which they will be doomed to virtual house arrest until the “besa” is lifted.

A Rwandan journalist wanted to know how effective mediation in such disputes can be, given that from her observation, the success of the Gacaca legal process in her country has been limited. In responding, Marston differentiated between the two situations, explaining that in Albania the mediator is not a judge, but rather more like a middle man who goes between the families until a mutually satisfying solution is reached. In some cases, the wronged family can regain the honor lost with the murder of its son or father by choosing to forgive the perpetrator, which places them on a higher moral ground. [Forgiveness was also a key element of the Gacaca, as portrayed in the 2009 film My Neighbor, My Killer and discussed in the September 2009 Storyboard article on the Munich Film Festival.]